Potter's Test for hip impingement (PHIT: Potter Hip Impingement Test)

Firstly, it is simply better recognised and therefore clinicians are making the diagnosis more regularly.

Secondly, there is gathering evidence (from comparative anthropological studies in sapiens skeletons) that we are 'evolving' shorter and thicker femoral necks, with the resultant capacity for femoro-acetabular 'knocking' during certain activities.

Thirdly, there is some evidence that the increasingly 'sitting' culture of the general population and particularly office workers, produces anterior capsular shortening, weakening of the Gluteus Maximus muscle, as well as the 'core' group of muscles. Indeed it is the author's hypothesis that, for those in whom FAI exists, the use of lordosis-supporting chairs or devices may in fact potentiate the problem by maintaining the acetabulum in an 'overhanging' position on the femoral neck.

Fourthly, the cohort of patients coming through have, historically, been very active in training from an early age particular in sports involving multiple axes of movement and loading to the hip joints eg football, tennis, hockey and rugby. It is hypothesised (and there is gathering strong evidence for) that the CAM lesion develops as a result of deformation of the femoral head/neck junction growth plate involving what is effectively a 'micro-slipped epiphysis'. In addition, there has been a significant increase in the uptake of sports and leisure activities which involve a lot of hip flexion, often over long distances (eg. long distance cycling, deep squatting and lunging, rowing, martial arts etc.) Furthermore, there has been a trend towards 'functional' training and yoga which encourages exercises that use extreme hip flexion, external rotation and deep squatting positions as part of their practise.

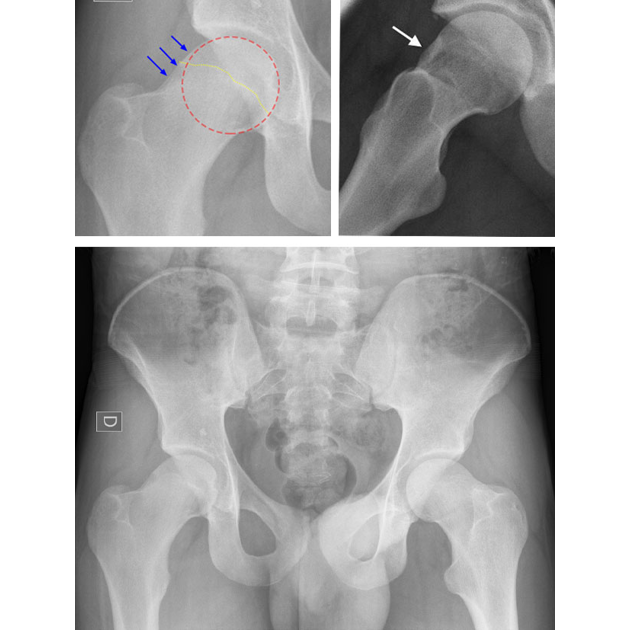

This results in increased actual and potential effacement of the femoral neck onto the acetabular rim. Resultant local joint irritation (synovial and capsular) occurs, with reflexic muscle adaptation and shutdown, as well as longterm kinematic changes in pelvic and hip control. Hence the classic symptoms of pain in a 'C' sign distribution. Its diagnosis is usually from radiographic evidence (to assess whether there is the presence of hip dysplasia or similar causes in change of hip morphology (CAM hip) or pincer impingement with labral damage) in combination with clinical examination. However in the authors opinion, FAI should always be considered a 'clinical' diagnosis (that is to say that it can exist without radiographic evidence). Copyright N.Potter

Clinical relevance

Until now traditional clinical examination has relied upon two primary tests;

The FABER (Flexion, Abduction and External Rotation) test and the FADIR (Flexion, Adduction and Internal Rotation) test. The Thomas Test has also been used to assess the degree of associated anterior hip capsule and flexor muscle shortening, commonly found in associated degenerative changes of the hip joint.

All of these tests are traditionally performed with the patient lying in a supine position. However the author postulates that though useful in the

clinical setting, these tests are flawed. The supine position does not take into account normal anatomical hip morphology and its positional relevance

nor the functional relationship between spinal lordosis and its maintenance, during hip flexion. This is particularly the case when the patient

is either in an upright seated position (with the hip in flexion) or when performing hip flexion when load-bearing eg gym, yoga climbing, rowing.

It is quite clear that many people get functional impingement in a seated position which is currently missed in their clinical examination.

Further importance of the test

The test bases itself on the relationship between the maintenance of neutral lordosis position in the lumbar spine and the available range of flexion movement in the femoro-acetabular joint whilst in that position.

Most subjects should be able to achieve at least 120 degrees of flexion (in the hip) before needing to flex the lumbar spine and 'rock' the pelvis to accommodate more movement. However, in those with FAI this may happen as early as 85 degrees of flexion.

In the author's opinion this has important ramifications in activities and sports where seated flexion is a required pattern of movement. Clinically, it has been shown to be very relevant to rowing and cycling. Strong evidence is developing that lumbar spine injury (in the form of intervertebral disc disease) or pars defect and/ or stress fracture and spondylolisthesis is much more common in those with a positive PHIT test.

Indeed 2 cases (footballers) of unexplained unresolving low back pain, the pelvic imaging showed significant CAM hip deformity for which the lumbar spine was compensating.

Clinical relevance

PHIT: Test description

The patient is in a seated position preferably on the edge and end of an examination couch. Their position is such that the examiner can easily stand next to the patient in order to palpate the patient's lumbar spine. The patient's hips should be at an angle to the pelvis of no more than 90 degrees, knees flexed and feet hanging.

The patient is asked to sit erect with a straight spine as far as possible. The examiner uses their hand to place the lumbar spine into a position of neutral lordosis. The patient is asked to maintain this position with or without the aid of the examiner. The patient is asked to bring the knee towards the chest slowly into hip flexion. (for best results the test should be carried out with the examiner passively moving the knee to the chest to eradicate any compensatory or adaptational movement. The examiner monitors the point at which the lumbar spine can no longer remain in lordosis and begins to flex. This is best done by using the first three fingers to palpate the interspinous spaces of L3-L5/S1. As the spine comes on to flex to accommodate femoral-acetabular apposition, the spaces can be clearly felt to widen (ie loss of lordosis).

This is deemed to be the 'endpoint' of the test. The patient should be able to reach hip flexion of at least 120-130 degrees without either:

- needing to externally rotate the femur to accommodate the acetabulum contacting the femoral neck or

- having to flex the lumbar spine to do the same

The test should be carried out on both sides for comparison. The non-symptomatic side may also have a decreased range of movement from the norm, but not be presenting symptoms.

The test is positive

- if the patient cannot maintain lordosis at at least 90 degrees of hip flexion OR

- if the patient has to externally rotate the hip to do so or

- If the patient experiences groin pain and decreased range of motion whilst maintaining lordosis

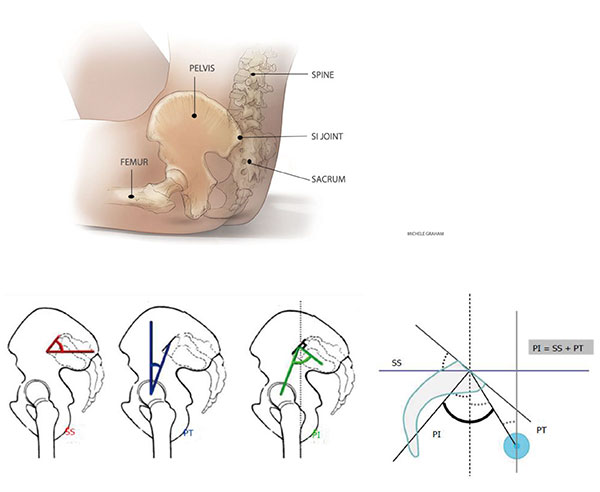

Pelvic Incidence

It has yet to be correlated but it is likely that there is also a direct relevance of the angle of Pelvic Incidence (PI) to the existence of FAI

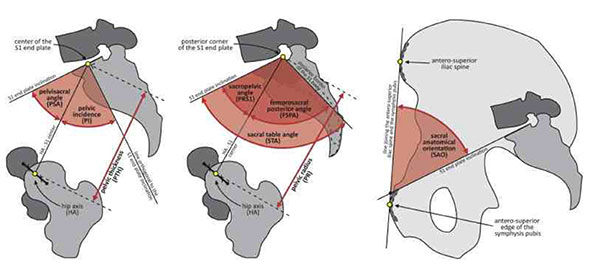

Diagram showing angular measurements necessary for calculation of pelvic incidence (PI) Copyright; NPotter

Diagram to show relative angular positions of the pelvic landmark anatomy and the effects of variance therein.

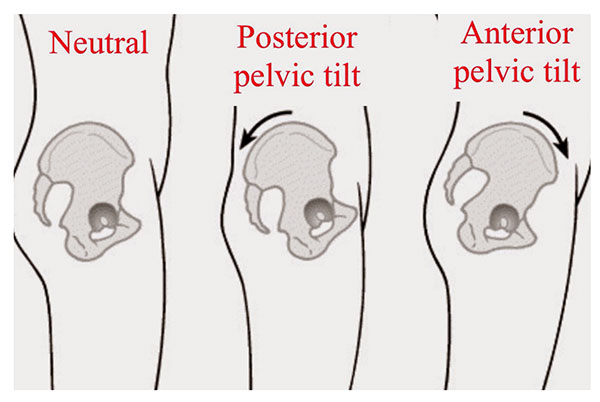

When pelvic incidence is low then the hip joint sits more vertically underneath the lumbar spine reducing the clearance possible between the femoral neck and the anterior-superior acetabular rim. The resultant effect is the need for pelvic posterior rotation (retro version) to accommodate the impingement. This is in turn effectively flattens the lumbar lordosis.

When sitting, the resultant retro version flexes the lumbar segments thus placing the posterior annulus fibrosus under strain contributing to early disc bulging and/or degeneration.

Diagram to show relative tilt effect induced by accommodation of FAI. The central diagram shows retro version. Copyright: NPotter